- Home

- Dudley Riggs

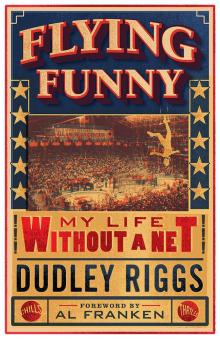

Flying Funny: My Life without a Net Page 4

Flying Funny: My Life without a Net Read online

Page 4

I was eight years old; my song and dance act was being retired. I was being “red-lighted.” Eighty-sixed. Run off. And my car was gone!

To his credit, Mr. Roddy later broke the news to me in person. But he took the long way around, looking past me as if I had an evil eye.

“I can always sell a bill with acrobats, jugglers, and a good, clean-talking comic,” he said. “But selling novelty acts is always hit-and-miss.”

He searched for a child-savvy example. “It’s like a teeter-totter. You were up this season, but when you are up, someone else has to be down.”

“Like me,” I said.

“You got to accept the odds, kid,” Roddy continued. “You climb the ladder of your career up a ways, then you slide back down, and then you climb up again, over and over, but you learn to not slide down so far. You’ve been up a long time, so now you’re going to be down for a bit.”

His face was fighting with itself. His usually pink nose had little bright red veins showing, and he looked like he was being tugged one way and pulled another. He didn’t feel good having to have this talk. I think he must have liked me more than Mother thought.

He ranted on uncomfortably, talking faster and changing his voice on every new thought; he went from embarrassed to quarrelsome. I could smell gin and cigar smoke.

“Big deal! You’re young! That’s life! You’ve made some money; you’ve had your moment. Always remember that when you worked, you got your laughs. Not many acts get the laughs you got.”

Then he talked himself right out the door of his own office. He gave me this parting shot: “We thought you might sing on until your voice changed. No such luck.”

I stomped my way back to the hotel, talking out loud about what I should have said. I didn’t get it. Why was I being tossed off the circuit? How could I go from a big deal to a nothing so fast? What was I? A show-business “has-been” before the age of nine?

At the hotel, Grandmother Riggs gave me a big hug. She was beaming. “Now you get to go to school.”

In the 1930s, my folks were playing the big-time vaudeville houses thirty or more weeks a year and easily filled the rest of the year with circus dates. They had their twelve minutes, a well-rehearsed and highly polished hand-balancing act, as well as a second act, a comedy acrobatic act, that worked in theaters and in the circus. They didn’t trust the twelve-minute creed. They continued to create new sketches and routines, always adding new acts to their roster.

My parents became well known for a short act that was only meant to cover “stage waits” but became their most popular offering, though the manager treated it as “cherry pie”—a filler act they performed for free. It consisted of a little five-foot-wide stage, like a fabric closet on wheels. The curtains were pulled aside to reveal two little figures, a man and woman with tiny bodies but with my folks’ full-sized heads. Doc and Lil called themselves “The Humanettes.”

The look of the act was very much in the style of a then-popular newspaper cartoon that featured tiny characters drawn with very large heads. They were presented as “Faces from the Funny Papers.” The doll hands were controlled by sticks and the feet were attached to little mallets, so that when they did a tap routine, the little tap-shoed feet would beat back and forth across the stage. This tiny husband and wife sang and danced on a miniature stage, set in “one”—meaning in front of the main curtain. They would be called upon to perform during major scenery changes, and it worked well, with some rehearsed music and a lot of improvisation. The producer expected them to fill the time needed to make the scenery shift—no matter how long it took—performing until the stage manager cued them that the next act was set to go on.

In full makeup, dressed up like a couple on their way to the Easter parade, this miniature marionette couple tapped the dance steps and sang a sweetly sarcastic song directly to the audience, all the while keeping an eye on the stage manager, who would signal if the next act was ready to go on.

Doc: I wrote a little song the other night

And put it on the shelf.

(Now are you on? Now are you on?)

Lil: Now any song that he can sing

He thinks he wrote himself.

(Now are you on? Now are you on?)

Doc: Now don’t pay any attention to her

She has an awful gall.

She thinks that she knows everything

When she knows nothing at all.

Lil: Well . . . how can I know anything?

When that thing knows it all?

(Now are you on? Now are you on?)

Jack Roddy often bragged, “When there is an accident in the circus, they call out, ‘Clowns!’ In vaudeville, they call up ‘The Humanettes.’” The Humanettes saved many performances by covering these unexpected stage waits, entertaining the audience so that the show could fix itself. Stagehands loved it; it saved their jobs. I, too, loved the act and how new it always seemed, and I’d play in the little stage myself in the wings between shows. After their three minutes of rehearsed song material, everything else had to be created on the spot: holding the crowd, inventing a moment of fun, presenting their “Faces from the Funny Papers” while staying in character and monitoring the crisis backstage. Riggs & Riggs would never have thought of their filler act as being something called “improvisational theater,” but that is exactly what it was.

3

The World’s Fair

“Are you with it?”

The opening of the New York World’s Fair in April 1939 was enormous. Advertisements used phrases like “A Century of Progress” and “A World’s Fair to Celebrate the End of the Depression.” My father did radio announcements for the fair in which he said, “The World’s Fair speaks to all Americans, pointing the way to a new beginning, an America on the threshold of a great tomorrow, an America made whole again through the wonders of science and the power of technology. Every American citizen should see and hear all that the World of Tomorrow predicts for our future, not the future thirty to fifty years ahead, but the future that starts tomorrow, this week, at the New York World’s Fair.” Because of his radio announcements, Doc became known as the Voice of the Fair.

On opening day, the mayor and other dignitaries joined President Franklin Delano Roosevelt on the podium. But I “knew” that it was Doc’s radio spots that really got people to come to the fair. Doc believed in the fair, just as he believed in what he called “the power of the public, the power of the people in the audience.” He enjoyed seeing their faces, enjoyed watching the spring in their step as they came down the ramp after seeing the World of Tomorrow exhibit with its futuristic cars and kitchens. He liked seeing people transformed by the fair’s message of hope and prosperity, and he believed in the humanity of what he called the “show-going public.” Doc was sold on the fair.

“We are in the business of entertaining that public, that’s what we do,” he would tell me. ‘‘We don’t grow corn, or make furniture, or sell insurance. All we can promise is a fewlaughs, some pleasant memories, and something to talk about tomorrow.” The World’s Fair offered the perfect job for my dad, something he was proud to promote because he really believed in it.

I was told that every “important” nation built pavilions to present samples of their country’s products, politics, and culture, all under the banner of “Peace and Prosperity.” Russia, England, Japan, and Italy all had pavilions. Italy spent more than a million dollars on an art deco modern palace celebrating Italian art, food, and an on-time rail system. Famous architects built futuristic structures with newly developed materials that evoked a future not just for America, but also for all the nations of the world. The message of these exhibits was that the future of the world looked bright.

The fair certainly made the future look brighter for our family. The fair provided two seasons of work—thirteen months over two years at top money.

“If this keeps up, we’ll all be able to get our teeth fixed!” Jack Roddy quipped.

The first sea

son of the fair bested all expectations for attendance. Billboards proclaimed, “It’s getting bigger and better every day. Don’t miss the New York World’s Fair!”

In the second season the public was happy, some even looking forward to going to the fair a second time to see the new 1940 additions. There was talk of making the fair a permanent year-round attraction. Hoping to make that happen, Mayor LaGuardia or some other political figure was on the fairgrounds every day staging publicity stunts for newsreel cameras.

All the circus and variety acts in the amusement area were expected to do free acts for these photo ops. The Ben and Betty Fox duo did their dance act on top of the Brooklyn Bridge. The Royal Hanneford Circus brought a beautiful Belgian horse to Wall Street for a photo captioned “Investment advice, direct from the horse’s mouth.” And my father did a handstand on top of the Empire State Building!

When I was eight years old, such events did not seem to be especially out of the ordinary. Using daredevil stunts to draw a crowd had become a popular form of show business advertising. “These free acts are just part of what we do for a living,” said Doc when people would ask, “Why? Whatever for? Are you crazy?” Like his father and grandfather before him, Doc was simply dedicated to entertaining the public.

On the way over to the Empire State Building the day of the feat, my mother had quibbled, saying, “You are such a company man, Riggs. Always willing to do free promotion and cherry pie.” She was being more than a little sarcastic about his having voluntarily taken the job. I could always tell when she was ticked at my dad; she’d add the word “Riggs” to the end of the sentence.

“If it sells tickets, it helps us. If the fair does well, we all do well.” He said it like he meant it. I guess he really was a company man.

Doc and I performed part of The Riggs Family Acrobatic Act in the Sky Lobby, located in the entrance of the Empire State Building’s observation deck, under a huge red, white, and blue banner that read “America Is High on the New York World’s Fair.” A small audience of confused sightseers applauded the unexpected show, then watched as the camera crew set up for Doc’s big finish. Everything had to go off exactly as planned if the photographers were going to get the shot they came for. We waited until they got just the right angle of sunlight. Then the photographers, safely belted on a scaffold platform, took pictures of Doc doing a chair handstand on the shoulder of the building, just below the observation deck. The platform allowed them to get bird’s-eye pictures of my dad pressing up to a handstand with the other buildings in the background, about eight hundred feet above the street.

My mother was a little edgy, not because of the height but because of the wind. She said it might gust enough to be a problem. She was holding my hand tighter than usual and was looking about, checking for anything that might be out of place. That was the first time in my life that I ever remember thinking that my father could possibly fall. I had seen him do the same handstand on the same chair for as long as I could remember, and we had worked these photo gigs on other buildings a few times before. But this was the tallest building in the world.

The breeze was just enough to blow Dad’s hair and pants cuffs. One of the newsreel guys said, “The wind blowing his pants really makes the picture.” A photo ran in the Sunday Rotogravure Magazine, and I heard that the one-minute fair promotion played in newsreel theaters from coast to coast.

In the cab on the way back to Queens, I sat between my folks. They were holding hands and talking sweetly to one another.

One day not long afterward Jack Roddy showed up backstage, looking like he had just come from a wake instead of the front office.

“Bad news. We have a holdback on payday.”

“Again?” said Doc. “Pardon me for saying so, but this is lousy timing.”

“But it’s hitting everybody, the whole country is hurting,” said Jack. “Just when we were pulling out of the basement, when everyone was looking ahead to better times, when people were feeling like they might have some little bit of a future.”

That was the beginning of a slow slide in morale that lasted all summer. The news abroad was getting everyone disturbed. The fair had lowered the admission price and cut back on salaries. The artists were supporting the enterprise with money earned but not received. Mother stopped looking for that house in Queens. There would not be a permanent World’s Fair.

The show kept going on, but the audiences were very tense. In the face of fear, what some thought to be satire was just actors working too hard for laughs that weren’t there. By now everyone was resigned to war. No grand tour, no show plans, no artistic breakthroughs could be made without considering war.

In 1940 the Italian Pavilion at the World’s Fair was gone, the red carpet was a year older, and the new uniforms that were added to the production numbers were not quite a color match. Still, the gates opened on time every day.

Gypsy Rose Lee’s Broadway show The Streets of Paris continued to be the big draw, but a new show called Twenty Thousand Legs under the Sea was edging her out with cheaper tickets and a woman in a very skimpy wardrobe who danced with an octopus. We were presenting fifteen vaudeville acts, two a day, three a day on weekends. But despite our long rehearsals and artistic efforts, the Parachute Tower amusement ride always had the longest lines.

A “girlie” grind show, doing five shows a day, starring an “old friend” of Doc’s, was getting most of the action at our end. Annette Delmar was featured performing a veil dance in front of a painting of Satan. One day, between shows, I got to peek in on the Satan Dance. Miss Delmar was not wearing any clothes at all that I could see.

“Now you know what the attraction is,” said my mother. “Attendance always rises in a direct ratio to the visible skin area of the feminine personnel,” said Grandmother Riggs.

The year before, the only naked flesh visible at the fair was under water, thanks to Salvador Dalí’s exhibit with a glass-enclosed pool framed on one wall. Nude “mermaids” would swim into view, giving ticket buyers a glimpse of a bare breast. This year you could get anatomy lessons all over the grounds.

If the 1939 fair had been a high-class look forward to a bright and happy future, the 1940 version fell back on nostalgia, patriotism, and sex. The ads read: “This year’s World’s Fair is dedicated to those common Americans, with simple American tastes.” Some people had said they stayed away the first year because they thought that they might not understand it or that they might embarrass themselves. They didn’t want to be “high-hatted” by those sophisticated artists and highbrow city planner types. Marketing downward worked to get in some bigger crowds, but they spent less money. For a while, business picked up, but it couldn’t last.

I was told that closing day set the record for attendance—nearly half a million people had made it out to Flushing Meadows. But although people had lined up for hours to see the World of Tomorrow, they just didn’t have enough time or money left once they got to us. Our little vaudeville show was not that big a draw.

“If they don’t want to buy your tickets, there’s nothing you can do to stop them,” the PR guy said. Doc managed to look confident, even when there was nothing coming in; he always acted as if a great amount of work was just around the corner. But for many of the other acts, confidence was in short supply. The backstage noise I overheard ran from grumbling and whimpering to outright agitation.

“This is just a bad location. No wonder we couldn’t draw flies,” said Mark, a juggler, one day. “Face it, this is just a rotten show!”

I remember Grandmother slamming down a makeup box. “You must never knock the show. If you are with it, you’re for it. If you’re not for it, then get away from it!”

Actors will fight with each other, and they’ll fight with the director and the playwright, but they do become loyal to the show. After a while they bond with each other to accomplish something onstage and that becomes stronger than everything else. This assumed real importance when we began to work improvisationally in the 1950s.

There were a lot of disappointments along the way. Luckily, there were actors willing to hang in there while we developed a new kind of theater . . . and were falling on our face. You had to be “for it” in order to get “it” off the ground.

4

TheRiggs Brothers Circus

Here today, gone tomorrow!

The World’s Fair had been such a big deal, and Jack Roddy said all that steady work had got us spoiled. “Now is the time for you to get with it, and find us some new bookings,” said my dad.

“I know how much you like good conditions and steady work,” Roddy replied, “but for you to get work today, you may have to take some split weeks or do some upping and downing . . .” He paused to make his point. “But at least you’ll be working.”

Jack was underestimating my dad, who had a bigger goal in mind.

When the producers of the World’s Fair settled up with the performers, they still owed Doc quite a bit of money because he had produced some of the shows. The owners made an offer to my father. They would sign over certain physical assets to cover much of the back salary still owed to us on closing day.

I still have the list of what Dad got out of the settlement:

Flameproofed canvas. Two 120-foot round ends and three 60-foot midsections, making a 300-foot-long circus big top—from O. Henry Tent and Awning Company.

Four 54-foot center poles, bailing rings, stakes, quarter poles, side poles, canvas sidewall, and a complete 40-foot marquee.

1938 REO Speedwagon canvas truck with trailer.

1938 REO semitrailer pole wagon, 72 feet long.

1935 Chevy seat wagon—stringers and jacks with 1 × 12 seat planks.

Flying Funny: My Life without a Net

Flying Funny: My Life without a Net