- Home

- Dudley Riggs

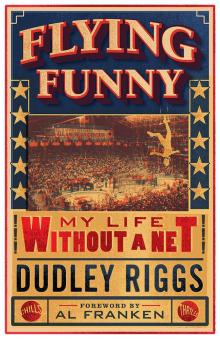

Flying Funny: My Life without a Net

Flying Funny: My Life without a Net Read online

Flying Funny

Flying Funny

My Life without a Net

Dudley Riggs

Foreword by Al Franken

University of Minnesota Press

Minneapolis

London

All photographs courtesy of the author, unless credited otherwise.

Copyright 2017 by Dudley Riggs

Foreword copyright 2017 by Al Franken

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Published by the University of Minnesota Press

111 Third Avenue South, Suite 290

Minneapolis, MN 55401-2520

http://www.upress.umn.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Riggs, Dudley, 1932– author.

Title: Flying funny : my life without a net / Dudley Riggs.

Description: Minneapolis : University of Minnesota Press, 2017. |

Identifiers: LCCN 2017014912 (ebook) | ISBN 978-1-4529-5453-0 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Riggs, Dudley, 1932- | Circus—United States—History—20th century. | Theater—Untied States—History—20th century. | Brave New Workshop (Minneapolis, Minn.) | Circus performers—United States—Biography. | Comedians—United States—Biography. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Entertainment & Performing Arts. | PERFORMING ARTS / Circus. | PERFORMING ARTS / Comedy.

Classification: LCC GV1811.R44 (ebook) | DDC 791.3092 [B] —dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016059307

The University of Minnesota is an equal-opportunity educator and employer.

This book is for Pauline,

my closest friend and loving wife,

now for more than a third of a century.

Contents

Foreword

Al Franken

Flying Funny

Introduction

1. The Polar Prince

2. Vaudeville

3. The World’s Fair

4. The Riggs Brothers Circus

5. School on the Road

6. The Circus at War

7. Flying Funny

8. Clown Diplomacy

9. Fliffus It Is!

10. Word Jazz

11. Never Let Them Know You Can Drive a Semi

12. Change the Act?

13. Yes . . . Please!

14. Instant Theater

15. The New Ideas Program

16. Theater without a Net

Acknowledgments

Plate Section

Foreword

Al Franken

In 1968, two geeky teenagers went to a show at a small revue theater in Minneapolis called Dudley Riggs’ Brave New Workshop. The geekier of the two, me, was a senior in high school. The other, Tom Davis, was a junior. That night we saw adult people doing what we wanted to do: perform onstage and make people laugh.

Tom and I had been writing and performing at school, teaming up to do morning announcements for laughs. Obviously, we had watched comedians on television. But for some reason, seeing live comedy on a stage made show business seem like a real option for two kids from Minnesota.

After the show, the cast did an improv set based on audience suggestions. Some of the stuff worked, some of it didn’t. But that’s what made it even more exhilarating when the performers scored. Improv techniques were also developing at the more famous Second City in Chicago after it opened in 1959, and Tom and I often referred to Dudley’s as Third City.

Tom and I kept returning for the improv sets, which were free. We quickly got to know the performers, who were really just a few years older than we were. After one of those sets, we met Dudley Riggs.

Dudley was an exotic figure for two suburban boys. He’s actually an exotic figure, period. A former vaudevillian and circus performer, Dudley evoked Professor Marvel from The Wizard of Oz. Bow-tied, slightly rotund, jovial, and, at the time, I think, someone who enjoyed an alcoholic beverage or two or three, Dudley was one of the first larger-than-life characters I’ve been fortunate (and in one or two instances, unfortunate) to meet.

Dudley took an interest in me and Tom and invited us to get up onstage on what, at most comedy clubs, is called “open mic night.” Except here the theater was so small there was no need for microphones. As a matter of fact, there were really no comedy clubs in America at that time. No places called The Punchline or Zanies or the Laugh Factory.

Tom and I got up on a Monday night—I think. I do remember getting laughs with our parody of a local newscast taking place on the night after the day of World War III. Dudley liked us and said he saw “sparks.” Holy moly!

Before long, we were doing our own two-man show at the Workshop, getting not only notes from Dudley but also money. We were professional comedians!

But off I went to college. During the summers, Tom and I would do shows at the Workshop. I also had a day job, working for my suburb’s street department, mowing grass and weeds around the water tower and other city property on an industrial-sized rider mower. The schedule started getting the best of me, and one night I got a terrible migraine before our show. I told Tom he might have to cover if I suddenly had to run backstage and throw up.

Fortunately, Tom had been working on a couple of monologues and pulled it off. The audience figured out what was going on and gave us a standing ovation at the end of the show. Dudley had been watching from the back of the house and came backstage to commend us. While I was lying facedown on a couch, Tom asked Dudley what would have happened if I’d thrown up on stage.

“The audience would have all left,” he said with the absolute assurance of a grizzled show-business veteran.

In the fall, I’d go to college, and Tom joined the regular cast at the Workshop, becoming a hilarious improvisational performer. I regret that I never had that improv training that Saturday Night Live cast members from John Belushi, Jane Curtin, Bill Murray through to Will Ferrell, Amy Poehler, and Tina Fey were all steeped in.

At the end of the summer between my junior and senior years of college, Tom and I hitchhiked from Minneapolis to L.A. We stayed with Pat Proft, a Brave New Workshop alum, who went on to cowrite the Naked Gun movies, the Police Academy movies, and tons of others. Pat got us a slot at The Comedy Store, a new stand-up club on the Sunset Strip, and suddenly our peers in the stand-up world knew who we were.

It was because Dudley recognized some “sparks” when we were in high school that Tom and I became Franken and Davis. After becoming writer/performers on SNL, we kept returning to Dudley’s to work out material that would find its way on the show.

Dudley couldn’t have been prouder of us. And I couldn’t be prouder of being an alum of his theater and a friend.

Flying Funny

I rosin my hands after I’m up the ladder. That way, none is lost in the climb. Besides, the ritual of powdering my hands builds audience anticipation. We buy solid rosin blocks at a music store. The deep amber intended for the bows of cellos and violins is crushed and placed in a clean white sock to become a rosin powder bag that makes my hands sticky and improves my grip.

As I prepare to fly, I focus on the little details, almost unaware of the crowd—the big picture—what I’m about to do. Then I release my feet from the platform, hop tall, point my toes, and fly. Now I feel the rush, the aliveness, the arousal, and the fun of flying.

Aerial acrobatics do not feel the way they appear to the audience. I do not see myself at this moment as a figure fluidly passing from one trapeze and flying into

the hands of another man swinging in the air. Instead, I concentrate on getting pumped, on getting plenty of air before taking the fly bar. The fly bar is heavy—a solid rod of steel—and when you take the bar it has energy, you have to be ready to go—it could pull you right off the pedestal if your balance fails. When the catcher wraps his legs into a Dutch Lock, I know it’s time. The catcher swings out and back, two swings to complete the geometry of my one longer arc. When he’s at the near end of his swing, “it’s showtime,” and I must go down the hill of space and meet him as he comes up to take my wrists.

It is surprisingly easy to forget the way it must look to the audience, the way it must feel to someone watching as we risk death for a living. The flying trapeze remains the most graceful, romantic act in the circus, and after many years of flying, I’m still a little astonished when I see someone else performing in a great flying act.

People are afraid of the unknown. Most people have a fear of falling. But flyers need to believe that is a learned fear. We don’t climb the circus ladder in fear. Gravity is a known constant—gravity is reliable—always there to power my swing. We aren’t nuts up there; we do have a respect for gravity.

And so when I take these steps, I climb the rope ladder, heels first, pressing against the sides to maintain tension. It’s what I know. Just as I know at what point my hands might start to sweat and defeat my grip. I know when I reach the top how to retrieve the bar, find the spot to stand, how far to lean back on the lines. I know these steps to the point that I don’t have to think about them anymore; it’s in my head and muscle memory. I’m not thinking, “Can I do this?” I’m thinking, “Hey, watch this!”

“Breathe positive and enjoy the moment,” Doc always said. Doc was my teacher, my trapeze partner, and my dad. “You are working for that moment when the crowd gasps, then cheers, the moment when fear gives way to exhilaration,” he said. “Face it, Son, flying is sexy.”

And risky. Pride plays an illusive role in the circus; arrogant pride can get you killed. You just don’t want to get too cocky. Just when you think you are the best, chances are you’ll blow it; you are not the best once you think you are—kind of a paradox, right? Flying tricks require subtle confidence and, of course, faith in what you are doing. You also need to remember why you’re up there: to entertain the public, to enjoy doing what they can’t do.

A flyer must have pride in his passes and faith in the catcher. The catcher is the one who really makes the act. A good catcher is valuable beyond measure, someone who just might save your life. He is someone who can straighten you out, untangle a mess you’ve made of a trick, and get you safely back to the bar so that you can take the applause.

“You are too tall to ever be a great flyer,” my flying coach, Freddy Valentine, once told me. “Your height works for you in the horizontal bar act—but for the flying act, you’re too tall to ball up in your tuck.” Fred, an old-time flyer, was wise and very honest. “Look, you can fly funny, all flailing arms and crazy legs, but you’re too damn tall to fly straight. Stick with comedy.”

Eventually I had to decide: to fly or be funny. Improvisational theater turned out to be both.

INTRODUCTION

“Show business is America, America is show business,” Billy Rose, the great showman, liked to say. Today, when show business is such a vast enterprise, it’s hard to believe there was a time when show business outside of the major cities meant only “variety show business”: vaudeville and the circus. All manners of entertainment—from dancers, acrobats, and jugglers to contortionists and hand balancers—performed with music but often without words. Silent, pantomime acts—“dumb acts”—were interspersed with singers, actors, and comedians. “Novelty acts,” a term that stripped away an act’s claim to ever be considered important, fit under the banner of “variety.”

Variety acts so dominated the field of vaudeville entertainment that the trade journal for show business was and is still named Variety. Of course, in big cities, there was also legit theater and opera, which offered high prestige, but often paid a lot less. Some stars found themselves taking home more money in Peoria than they could in New York. It was okay to brag about your European tour, but not a good idea to talk up those twelve weeks playing small houses in all of those inland states where most of America’s food comes from.

My parents were performing in vaudeville in Little Rock, Arkansas, when I was born. My crib was a hotel dresser drawer, and my nanny was Albert White (known as Flo), a male–female clown. As soon as I was able to sit up, they cast me in the circus—parading in a pony cart. My life in show business began.

So far I’ve had three show business careers. In my adult life, I produced and directed more than 250 original live theatrical productions at Dudley Riggs’ Brave New Workshop. Known as the nation’s oldest ongoing satirical comedy theater, Brave New Workshop still today presents social and political satire in revue format year-round. Many of America’s greatest comedy artists, writers, actors, and producers learned the art of improvisation on my stage before going on to fame and fortune.

That list is long. It includes Louie Anderson, Avner the Eccentric, Del Close, Mo Collins, The Flying Karamazov Brothers, Franken & Davis, Lorna Landvik, Carl Lumbly, Peter MacNicol, Pat Proft, Penn & Teller, Stevie Ray, Sue Scott, Rich Sommer, Nancy Steen, Steven Schaubel, Faith Sullivan, Peter Tolan, Linda Wallem, and Lizz Winstead. The theater—now known as the Brave New Workshop Comedy Theater—continues to make me proud. But these years spent producing and directing at the Brave New Workshop were actually my third career.

My first career was as a child star in vaudeville, and my second was as a fearless circus flyer. I performed for the Russell Brothers Circus, the Blackpool Tower Circus (England), Cirko Grande (Havana, Cuba), the Al G. Kelly & Miller Brothers Circus (USA), Stevens Brothers Circus (USA), the Dolly Ja‑cobs Circus (Canada and Alaska), the E. K. Fernandez All-American Circus (Japan), and the Grande Cirko Americano (Puerto Rico). In vaudeville, I performed on the Barnes and Caruthers, Shubert, and Sacco entertainment circuits, throughout the United States.

I had loving parents, helpful uncles, and a grande dame of a Victorian grandmother who would only bring out her crystal ball if other family members couldn’t get work. Adults treated me like an equal, as long as I hit my mark on cue. Because my family was always on the road, I never had a hometown. For me, “home” was where the work was.

I grew up listening to nineteenth-century circus music, abiding by the rules of the highly organized, glamorous, immensely complicated business that thrives on tradition, wondrous hyperbole, and the command of the ringmaster. The circus runs on rules.

In college I discovered and became overly fond of modern jazz, which seemed above rules. My mind’s ear was filled with jazz and circus music but crowded by a stubborn, recurrent notion I had of creating an original scene onstage while performing it.

“Theater without a script,” created by the actors through “free association,” was a concept from psychotherapy just entering my thinking in the 1950s. This would be theater of words not memorized from a script written by someone else or from some other time and place, but words discovered by the actors themselves. Words made up spontaneously in performance, not contrived in advance for performance. People said . . . that’s an insane idea.

It took time, crazy dedication, and a few evictions to build an audience for this new kind of theater. It took actors willing to trust me, take the risk, listen, cooperate, and trust their talent. Actors who want to work this way are finding places that encourage them now, but we went through a long phase when actors were screaming inside for an audience but had no place to perform. What actually started out as a tool to cover stage waits in vaudeville and control drunks in a nightclub audience became a new way to communicate and entertain.

My life has been constantly in motion, toward mostly unplanned goals: testing, evolving, curious about the next surprise. Happily seeking satirical targets and exposing vice and folly. Always looking

for fresh minds, talented artists, new ideas, and astonishment. Keeping my “suitcase act” always at the ready.

What follows is the story of a boy growing up in the rigid tradition of the circus and in vaudeville, and the unconventional education that prepared him for forty years of producing comedy theater, experimenting, and eventually developing a way to work improvisationally.

It would seem an unlikely path to travel from the exacting traditions of the well-ordered circus to the “no rules” philosophy of the improvisational stage. But both must entertain. And start on time.

1

The Polar Prince

The amazing aerial artists, Riggs & Riggs, performed their uniquely romantic, and dangerous pas de deux on the high trapeze. This young married couple has toured in circuses internationally, always with top billing and income, striving to be the best double trapeze act in the world. In America they are always placed high over the center ring.

—New York Post, April 11, 1928

I was born as planned during the off-season. My arrival on the coldest day in January 1932—in the bottom year of the Great Depression—was a conscious, perhaps imprudent, decision on my parents’ part after five years of marriage during bad economic times. I know all of this because of my mother’s constant reminder: “Always remember, you were born a very much wanted child.”

I was soon touring the country with the Russell Brothers Circus, a large motorized circus, a big “mud show.” It was one of many such shows during the golden age of circus. In the 1930s and 1940s there were dozens of circuses in America, all smaller than the Ringling Brothers or Cole Brothers, but by no means tiny. They all had the requisite three rings expected by the public with lions, tigers, elephants, and clowns. A great American tradition, mud shows brought education and entertainment to the small towns that were passed over by the grand railroad-mounted circuses. My folks originated a beautiful but risky high aerial double trapeze act performed forty feet in the air without a net. The announcer proclaimed “beauty and danger aloft”—so that all eyes wouldbe on Riggs & Riggs.

Flying Funny: My Life without a Net

Flying Funny: My Life without a Net